Despite limited progress, COP29 yielded some outcomes related to displacement. Here are five displacement-related outcomes from COP and a preview of three issues requiring specific attention in 2025.

- The new climate finance goal: A missed opportunity for loss and damage but a partial recognition of vulnerable groups

The final text “urges” Parties to promote the inclusion of vulnerable groups, including migrants and refugees, in climate finance efforts. Although internally displaced persons (IDPs) are not explicitly mentioned, this language creates a potential avenue for channelling climate finance to prevent and respond to internal displacement through the Fund for Responding to Loss and Damage – which already includes displacement, planned relocation and migration in its scope – and other funding arrangements.

2. The Fund for Responding to Loss and Damage (FRLD) is now operational

The completion of the operationalisation of the FRLD at COP29 so it can begin financing projects by 2025 is a significant milestone..

Positively, the scope of the Fund remained unchanged in Baku, maintaining the inclusion of “displacement, relocation and migration” agreed at COP28. The Fund is an opportunity to finance prevention and responses to displacement, as well as durable solutions for people displaced in the context of climate change and disasters. It also recognizes displaced persons and migrants as beneficiaries of climate funding and encourages their participation in the design and implementation of supported activities.

Supporting the Fund to address displacement will require further evidence on the scale, duration, and impacts of displacement, alongside more robust assessments of associated costs. IDMC and partners are committed to supporting these efforts, offering technical assistance to countries and contributing through mechanisms like the Santiago Network for Loss and Damage (SNLD).

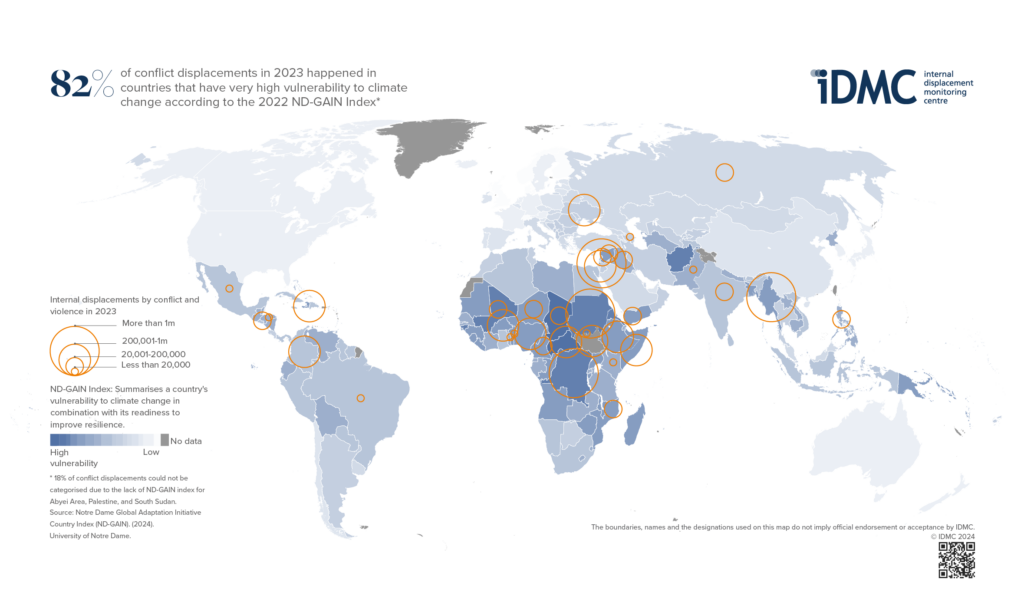

3. Progress towards addressing the overlap between climate, conflict and displacement

In 2023, 82 per cent of conflict displacement occurred in countries with high climate vulnerability, yet these countries receive disproportionately low levels of climate finance. According to a UNHCR report, produced in partnership with IDMC and others, fragile states receive just $2 per person annually for adaptation, compared to $161 in non-fragile states. Addressing the nexus between climate change, conflict and displacement urgently requires increased investment and coordination.

The launch of the Baku Call on Climate Action for Peace, Relief, and Recovery in Baku is an important step towards outlining paths for addressing climate change, conflict, and humanitarian needs as interconnected challenges, including through the establishment of the Baku Climate and Peace Action Hub, a platform to integrate climate and peacebuilding efforts.

The Call acknowledges displacement as a critical issue, identifying its links to water scarcity, food insecurity, and land degradation. It also advocates for equitable resource management to address displacement, improved data and analysis on human mobility and enhanced efforts to protect displaced persons in the context of climate change.

4. Advancing displacement considerations in the adaptation and mitigation workstreams

Displacement also continued to gain attention in discussions related to adaptation and just transition pathways. COP29 made some progress on operationalizing the Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA), with negotiators agreeing to develop a maximum of 100 indicators to measure progress on adaptation under the UAE-Belém work programme. Mobility-related indicators, such as IDMC’s Global Internal Displacement Database (GIDD), are included in the current draft list. The final list of indicators needs to be completed by COP30 in 2025. It will be essential to maintain indicators that help monitor progress in addressing displacement and migration.

Although COP29 deferred a formal agreement on the UAE Just Transition work programme to COP30, its draft text highlights the importance of including migrants and IDPs in social dialogue. Recognising these groups’ unique challenges and contributions to the green economy is essential for ensuring that transition pathways are inclusive and equitable, and for avoiding risks such as arbitrary displacement or forced labour.

5. Rising visibility of displacement at COP29

Beyond the formal negotiations, human mobility is also becoming increasingly visible in the parallel events and discussions at COP29. In Baku, two dedicated pavilions—the Climate Change and Human Mobility Pavilion managed by the International Organization for Migration (IOM) and the Climate Mobility Pavilion of the Global Centre for Climate Mobility (GCCM)—hosted numerous events. From loss and damage to adaptation, finance, data and technical support, the discussions explored displacement and other forms of human mobility in the context of climate change.

IDMC brought its expertise and actively engaged in Baku, advocating for displacement to be a key consideration in relevant negotiation workstreams. It also partnered with other organisations to develop joint messages for COP29, and coordinated daily briefings of the Advisory Group on Climate Change and Human Mobility. Together, we pushed for the inclusion of human mobility in relevant negotiation texts. We also organised and participated in several side events, emphasising the need for enhanced data collection and displacement risk modelling as well as analysing the nexus between climate change, displacement and conflict, or with loss and damage.

(Article courtesy of IDMC. Read the full article on https://www.internal-displacement.org/policy-analysis/cop29-key-outcomes-on-displacement-and-implications-for-climate-policy/ )